Research into finding detours for cognitive obstacles, part I

Grant awarded, application shared

26th of June 2020

Approximately a year ago, I formulated a personal mission:

I have made it my personal mission to collect detours to cope with the neuropsychological symptoms of Parkinson’s. I hope to turn the insights I gain from such a collection into concrete tools which will increase understanding between patients and their loved ones. Mental freezing is more diffuse, less concrete, more of a taboo, less researched, less visible and also simply less sexy than motor freezing. That is unjustified because the impact of mental freezing on the quality of life is huge. After all, you can disappear as a person | Marina Noordegraaf, 29th of May 2019, in a blog about depression and Parkinson’s

Last Monday – on the 22nd of June 2020 – my co-applicants Edwin Barentsen, Ingrid Sturkenboom, Esther Steultjens and I got the good news. The Dutch Parkinson Association has decided to honor our grant application! I consider it a great honor that our project is one of the lucky ones. The trust that has been placed in us and the responsibilities that go with it, I take on with solemnity.

Our application in 1 paragraph

If I only had one paragraph, I would summarise our application as follows:

A significant proportion of people with Parkinson’s disease suffer from obstacles in cognitive functioning, often even before diagnosis. These include problems with attention and concentration, memory, speed of thinking and acting, keeping an overview and planning, processing stimuli, and performing (double) tasks. In our research, we want to reveal and exploit the collective wisdom of people with Parkinson’s disease and their partners in circumventing these types of cognitive obstacles. We do this by retrieving the strategies used, arranging them according to scientific theories, and then handing them out again in the form of a practical self-help tool.

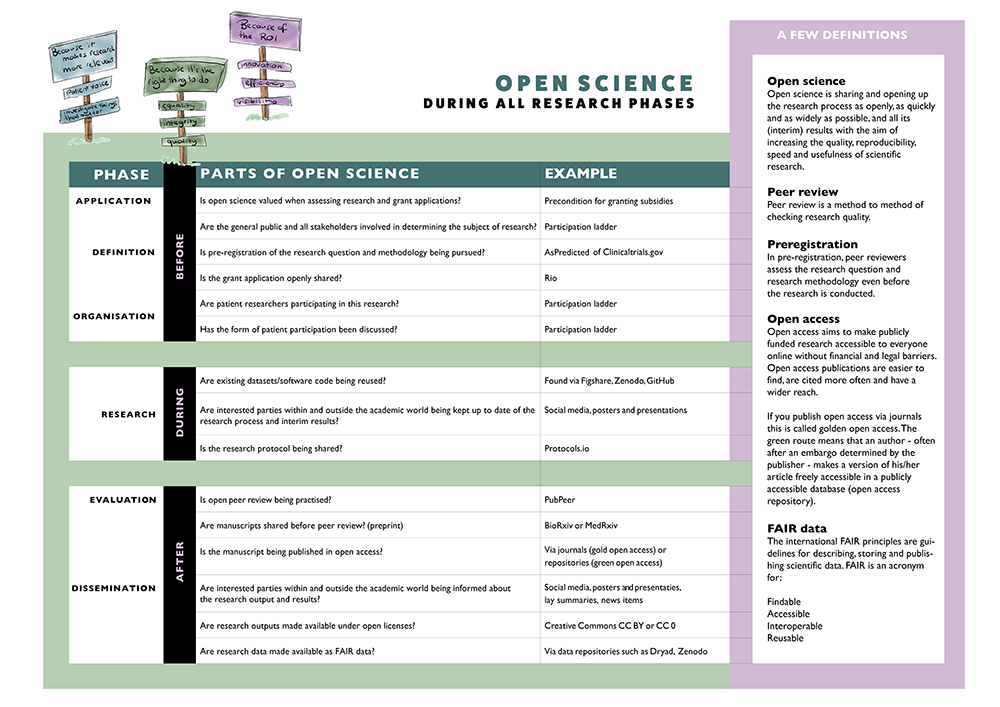

Our research project and open science

Science isn’t only about what you investigate, but also about how you investigate. I’m not just referring to the research methods, but also to the degree of openness you maintain in communicating about the research process and the research results. As readers of this blog probably know, I am a great advocate of open science. I intend to make this research as open as possible and that includes – to begin with – the open sharing of the research application (If you scroll down, the entire application will appear).

I expect to learn a lot during this research: not only about bypassing cognitive obstacles but also about open science. I am already experiencing a mismatch between the current system of subsidy applications and open science. After all, obtaining a subsidy is a very competitive business and that doesn’t really fit very well. Open science is about the added value of sharing and collaborating, of consciously looking for cross-fertilization, of starting from trust instead of from competition and letting fear that someone might run away with your idea guide you. But before you know it, you’re throwing yourself at the prize… just like me… and you’re one of the lucky ones…

However, I know all too well what other great proposals didn’t make it to the finish line. And that bothers me. Why us, not them? An awful lot of valuable research time and money is lost in writing applications that will never be realized. You’d think there just isn’t any other way. After all, there is only so much money available. But that’s not necessarily true. Research shows that a more even distribution of research money across all stakeholders is possible and can bring great benefits (Vaessen, 2017).

Fortunately, more and more researchers are openly sharing their grant proposals, including those that have not been honored. This has various advantages, such as:

- The potential for interaction and collaboration is increasing and with it the innovation potential;

- It becomes easier to build on rejected proposals;

- The claims made in various research proposals can be analysed using data mining, which in itself provides valuable new information.

Ideally, I would have shared the research proposal even earlier than now. On a smaller scale, I did and the benefits were obvious. For example, we have an advisory committee and some of the members submitted their own project to the Dutch Parkinson’s Foundation. One of them, Dr. Annelien Duits, told me that her proposal overlapped with ours and so we referred to each other. Had we known about each other’s plans at an even earlier stage, we might have been able to co-create a new application. Co-creation is so much easier if you know what others are doing.

There is room for more transparency in the process of grant review, which would strengthen the case for the efficiency of public spending on research ….. Once a good number of proposals are open, lots of other changes towards openness would follow across the entire research system | Mietchen, 2014

The application in its entirety

And here she is, for the enthusiast: the application in its entirety (the original application was in Dutch, so some information may be lost in translation)

COPIED-study

Cognitive Obstacles & Detours in Parkinson’s: Information Processing Tips for Every Day

A study of compensation strategies from a patient perspective

What is just as annoying is that I have almost lost my qualities of planning, multi-tasking (double tasks) | Peter van den Berg, 1st of january 2020 in a Dutch blogpost

- Drs. Marina Noordegraaf, researcher/designer, Verbeeldingskr8

- Edwin Barentsen, MBA, advisor

- Dr. Ingrid Sturkenboom, occupational therapist/researcher, Radboudumc

- Dr. Esther Steultjens, lector neurorevalidation, Hogeschool Arnhem en Nijmegen

All located in the Netherlands

Cognitive obstacles & detours in Parkinson’s disease. A study of compensation strategies from a patient perspective.

With this design-oriented, applied research project we want to visualize and utilize the collective wisdom of patients and their partners in their daily handling of the cognitive obstacles that Parkinson’s disease can entail. We do this by collecting, organizing, and sharing the strategies that patients themselves use. The ultimate goal of the proposed research is to increase self-reliance in circumventing cognitive obstacles.

Sub-objectives are:

- An in-depth inventory of cognitive obstacles and detours in processing information in people with Parkinson’s disease.

- Linking the detours found to scientific theories about daily functioning and the use of cognitive strategies.

- Development and implementation of a scientifically based self-help tool with detours for cognitive obstacles in Parkinson’s.

| Name | Institution/residence | Role in project group |

|---|---|---|

| Project supervision | ||

| Dr. Ingrid Sturkenboom | Radboud UMC, rehabilitation department of the ‘Expertisecentrum Parkinson en bewegingsstoornissen’/Nijmegen | Supervisor (occupational therapist and post doc researcher, expert occupational therapy ParkinsonNet International) |

| Dr. Esther Steultjens | HAN, lectureship neurorevalidation/Nijmegen | Supervisor (associate lector neurorevalidation and expert in cognition in daily activities) |

| Project execution | ||

| Drs. Marina Noordegraaf | Verbeeldingskr8/Nijmegen | Researcher*, designer, patient expert |

| Proces supervisor | To be recruited | Supervisor focusgroup meeting of two hours) |

| Research assistent | To be recruited | Research assistence (expert in the field of qualitative analysis methods) |

| Students HAN | HAN | Assistent during interviews |

| Advisory board | ||

| Edwin Barentsen, MBA | Dutch Parkinson Foundation | Advisor, patient expert, trainer of the training by the Parkinson’s Foundation with the title: Parkinson? Houd je aandacht erbij!’ (P?HJAE!) (which means so much as ‘Parkinson’s? Watch your head!’ (Freely translated :-)) |

| Dr. Annelien Duits | Maastricht University | Advisor neuropsychology |

| Prof. dr. Odile. van den Heuvel | Amsterdam UMC (loc VUMC) | Advisor neuropsychiatry |

| Dr. Jorik Nonnekes | RadboudUMC/Nijmegen | Advisor rehabilitation medicine |

| Prof. dr. Bastiaan Bloem | RadboudUMC/Nijmegen | Advis0r neurology |

| Mr. Peter van den Berg | Leg-uit | Advisor, patient expert, editor and co-author of the Dutch book: ‘Een nieuwe uitdaging met Parkinson. Praktische gids voor (jongere) mensen met de ziekte van Parkinson en hun omgeving’ |

| Simone Rensen | Helmond | Advisor, coordinator Jong Parkinson Inn, Helmond |

| Ad Nouws | Ad Nouws hulp bij Parkinson | Advisor, psychologist. Author of several books on the cognitive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Around 1990 Ad Nouws developed P?HJAE! and he supervised it for about 15 years. |

* Marina is an organic chemist by education and has experience in life sciences research. Marina has already completed the GCP (Good Clinical Practice) basic course – mandatory for working with test subjects. In addition, she is self-taught and will follow a course in ‘qualitative research’ before the start of the research. Furthermore, she is supervised on a daily basis by the department of neurorehabilitation and the occupational therapy department of the Radboudumc. Both have extensive expertise in conducting qualitative research.

A significant proportion of people with Parkinson’s disease suffer from obstacles in cognitive functioning, often even before diagnosis. These include problems with attention and concentration, memory, speed of thinking and acting, keeping an overview and planning, processing stimuli, and carrying out (double) tasks. At this moment, research and treatment mainly focus on the – more visible – motor symptoms. Although attention for cognitive symptoms is growing, this does not yet lead to scientifically substantiated, practically applicable tools for the cognitive obstacles that patients experience in daily life.

In the meantime, the Parkinson’s Association is running the ‘Parkinson’s? Keep your head! (P?HJAE!)’ training for about thirty years now. This training is intended for people with Parkinson’s who encounter cognitive obstacles during their daily activities. As preliminary research for this grant application, in the autumn of 2019, patient expert and P?HJAE! trainer Edwin Barentsen, together with the P?HJAE! course participants, listed the cognitive activities they mainly struggle with. The detours used by the patients themselves were also mapped out.

The applied scientific research for which we are applying for a grant builds on the patient perspectives collected during this inventory. We want to categorise the collected cognitive obstacles and detours using the validated PRPP model (Perceive (perceive), Recall (remember), Plan (plan) & Perform (execute); see point 7 of this application for a further explanation of this model for information processing in daily practice). A focus group meeting and an inventory survey will then help us sharpen the nature of the cognitive obstacles and detours of people with Parkinson’s disease.

The research results are processed in a self-help tool. After we have determined the use and usability of the tool through qualitative research, an improvement follows. The improved version will be distributed among patients and their environment who can use the tool to exchange tips from fellow patients and their families. The intended self-help tool supports people with Parkinson’s disease to keep on participating satisfactorily in society for a longer period of time.

| Duration | 18 months |

| Scheduled start date | 1-10-2020 |

| Scheduled end data | 1-04-2022 |

Background and relevance

Changes in cognitive functioning are common in Parkinson’s disease (Goldman, 2015; Ceravolo, 2012; Wen, 2017; Santagelo, 2015). In fact, changes in executive functions – a series of cognitive processes necessary for goal-oriented behavior – have often occurred some time before diagnosis (Fengler, 2017). In particular, people with Parkinson’s disease report problems with orienting attention, planning and cognitive flexibility. (Koerts, 2011; Kudlicka, 2018).

Problems arise in daily functioning if a person does not apply the right cognitive strategies to perform a certain task (Sturkenboom, 2019). Obstacles in daily cognitive functioning can lead to misunderstanding and early loss of full participation in society.

Treatment and guidance for cognitive obstacles

Several scientific studies have been / are ongoing on interventions in dealing with cognitive obstacles in Parkinson’s. The COGTIPS study assesses whether an online training can influence thinking problems (the data is now being analyzed). And recently studied strategy training courses are positive, but they do not yet provide sufficient evidence of effectiveness (e.g. Foster 2018; Giguère-Rancourt, 2018; Vlagsma, 2018).

Two of the applicants for this grant (Sturkenboom and Steultjens) focus on the development and evaluation of targeted, personalised cognitive strategy training to improve the performance of daily activities of people with Parkinson’s (Sturkenboom, 2019). They use a theoretical model of information processing, the PRPP model (Chapparo, 2017).

The model contains 35 applied cognitive strategies that people need to perform activities (see illustration below for an artist impression). The PRPP-assessment is an observation instrument belonging to the model. This assessment reliably measures how well someone carries out a daily activity and which cognitive strategies they use. The value of this assessment has also been determined for Parkinson’s disease (Van Keulen-Rouweler, 2017).

Patient perspective and needs in case of cognitive obstacles

The quality of life of PwP and their relatives is limited mainly by so-called non-motor symptoms (Tarolli, 2019). There is a growing awareness that cognitive obstacles in Parkinson’s disease require attention (Vlagsma, 2016; Kalbe, 2018), but that doesn’t translate into practical tools for today’s patient. That patients are in need of such tools manifests itself in e.g.:

- A scientific report from a multidisciplinary symposium on unmet cognitive health needs in Parkinson’s disease (Goldman, 2018).

- The well-attended training sessions of the P?HJAE! course of the Dutch Parkinson Association itself.

Detours are ways found by patients themselves to bypass cognitive obstacles. Think of changing behaviour, changing task demands or adapting the environment. At the moment, we do not yet have sufficient scientific insight into the detours used by patients themselves. This research proposal aims to better map those self-designed ways of circumventing cognitive obstacles and link them to effective interventions.

The mapping, is already partly done during the course P?HJAE! As preliminary research for the COPIED study, at the end of 2019 Edwin Barentsen organized an extra meeting that is not (yet) facilitated by the current course. His students thought up detours around an obstacle in small groups. They indicated that this was one of the most valuable sessions because it was only then that they saw the bigger picture of categories of obstacles, symptom amplifiers, and detours. (Symptom amplifiers are conditions that provoke or exacerbate cognitive obstacles, such as, for example, a busy environment with a lot of noise or not taking medication on time. (Also see the Dutch book ‘Mentale kwetsbaarheid door parkinson’ by Ad Nouws)).

In our research, we will be mainly looking for the strengths of people with Parkinson’s disease. By linking the insights from P?HJAE! with the PRPP model, we provide insight into how you can use the capacities you do have in everyday situations.

Research questions

Our research has the following questions:

- What cognitive obstacles (in terms of perceiving, remembering, planning and carrying out daily activities) do patients experience in their daily lives?

- Which detours do patients (and their partners) use to deal with these obstacles and possible symptom enhancers?

- How can we translate the collected detours into a practice-tested self-help tool for daily use?

Methods and instruments

Design-oriented (applied) scientific research with a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods. This type of research is not primarily about the truth, but about “improving” from a patient perspective. This solution-oriented form of scientific research not only describes problems but also provides effective principle solutions. Accountability is based on how it works in practice.

- STEP 1:

Preparing, holding and developing two focus group meetings (n = 16, divided into two groups)

Goals

The focus group meeting is aimed at assessing and deepening the inventory cognitive obstacles, symptom enhancers, and detours made during the additional P?HJAE! training session in December 2019. We will not only retrieve input about the experienced obstacles and detours themselves but also about the process of surfacing them. We want to know how – in the inventory survey that follows – we can ask questions that align as closely as possible with the daily situation of the patient.

Preparation

The meeting is prepared by putting the inventoried obstacles, symptom enhancers, and detours from the training P? HJAE! alongside the validated PRPP model (Van Keulen-Rouweler, 2017). By linking the general questions from the structured PRPP interview – developed with the validated PRPP observation instrument – to examples of patients, we focus the questions on people with Parkinson’s.

Selection of research participants

When recruiting for the focus group meeting, we strive for sufficient diversity (gender, age group, patient/partner, nature, and severity of the disabilities experienced). The participants are recruited specifically via the network of the advisory board.

Inclusion criteria are:

– a diagnosis (idiopathic) Parkinson’s disease or partner of someone with Parkinson’s.

– experiencing cognitive limitations in daily functioning, due to Parkinson’s.

– willing and able to travel to and participate in a two-hour meeting.

Exclusion criteria are:

– people who attended the extra ‘detours meeting’ during the autumn 2019 edition of the course P? HJAE!

All participants sign an informed consent for participation in the focus group.

Focus group meetings

During two focus group meetings of two hours, we collect cognitive obstacles, symptom enhancers, and detours in two ways. We start with open questions and compare the results with a more focused way of asking questions, as prepared using the PRPP method. The meeting is led by the principal investigator and an experienced process supervisor. Two observers provide their views on process and content in writing – and independently of each other – to the principal investigator.

Data collection and analysis

The meeting is recorded (audio) and a pseudonymised transcript is made of the parts that are relevant to the research question. The observer’s transcript and feedback are coded according to the category of said obstacles/detours. Here we take the categories of the PRPP method as a guideline and we are consciously open to categories that do not fall into the model (combination of deductive and inductive coding (Hsieh, 2005; van Staa, 2010)). The coding is done by the principal investigator and the research assistant, independently of each other. They then discuss the coding until agreement is reached. In addition, there is a reflection on the process. (Atlas.ti is used for data analysis). - STEP 2: Design of the survey, deployment, and analysis

With an inventory survey, we investigate whether the identified obstacles, symptom enhancers, and detours are recognizable for a larger group of people with Parkinson’s. The survey partly consists of closed questions in which patients and their relatives indicate to what extent they recognize an obstacle and detour (quantitative data). In addition, we ask for open questions and in-depth information (qualitative data).We develop the survey questions based on the themes we pick up from the focus group and the questions from the existing structured PRPP interview. The survey developed specifically for Parkinson’s is submitted to the advisory group as mentioned in point 4 of this document. Their feedback is processed in a new version.

In addition to the survey, we will send the research participants a short functional questionnaire – validated for Parkinson’s disease: The PD-CFRS (Parkinson’s Disease-Cognitive Functional Rating Scale). This questionnaire measures relevant functional changes related to mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s (Kulisevsky, 2013; Ruzafa-Valiente, 2016).

Selection of research participants

The survey and the PD-CFRS questionnaire are distributed among people with Parkinson’s and their families through the Dutch Parkinson Association, the Flemish Parkinson League, the network of our advisory board, and ParkinsonNext.

Data collection and analysis and preselection step 3

The survey does not ask for personal data that can be traced back to the participants. Via a separate link, we ask whether research participants want to test the self-help tool – which is developed based on their input – at a later time. If they wish, they enter name and contact details that we only use for this purpose. We indicate that we will contact them by telephone at a later date and that, given the diversity we are striving for and a possible over-registration, they may not be selected for the practical test/evaluation. After the closing period of the survey:

– the quantitative data will be descriptively analyzed.

– the qualitative data is thematically analyzed according to the type of cognitive obstacle/detour and where appropriate linked to theories of applied cognition/information processing. Coding and categorization are done independently by the principal investigator and the research assistant. They then discuss the results until agreement is reached and present this to the supervisors of the study.

-

STEP 3: Design prototype self-help tool

A self-help tool is developed with the results from the focus group meeting and survey. Depending on the research results, this can take the form of a poster, quartet, app, etc.

- STEP 4: Evaluation of the use and usability of the self-help tool through semi-structured interviews

The tool is distributed – with clear instructions for use – to n = 15 (15 patients and, if possible, their loved ones). After two months of use, we conduct a semi-structured in-depth interview with the participants, in principle at their home.

The questions are about the use of the self-help tool (including how often has it been used, which parts are mainly used) and the usability (including what is the perceived usefulness, how understandable is the tool, what do the participants think of the form). We expect to reach a saturation point with n = 15 (Guest, 2016).Selection of research participants

Research participants are recruited in step 2 via a separate link to the survey. We strive for sufficient diversity (gender, age group, patient/loved one, and severity of the disabilities experienced). This is done by telephone screening of the applicants, after which the selected participants sign an informed consent for participation in the practical test/evaluation. If necessary, we complete the selection by asking around the network of the sounding board group and/or by approaching a number of neurologists in various hospitals.

Data-analysis

The interviews are recorded (audio) and pseudonymized transcripts are made of the parts that are relevant to the research question. The qualitative data is thematically analyzed inductively by coding and categorizing the data (Hsieh, 2005; van Staa, 2010). This is done separately by the principal investigator and research assistant, after which they jointly reach a consensus. The quantitative data (how often used and which parts are used) are analyzed descriptively. -

STEP 5: Adjusting and implementing the self-help tool

With the results from step 4, the self-help tool is adjusted where necessary.

The scientific article is written and made available via a preprint server, after which it is submitted to a scientific journal for publication. The other activities that should lead to the widest possible implementation of the tool in daily practice are discussed under point 8 of this application.

Planning

Q3 2020: Preparatory work

- Write out and visualize the 35 PRPP score items and link them to the patient perspectives from P?HJAE!

- Preparing and submitting the research protocol and data management plan to the medical ethical committee.

Q4 2020 and Q1 2021 : Focusgroep bijeenkomst en ontwerp enquête

- Pre-registration research design.

- Design, organize and develop focus group meeting.

- Develop survey.

Q2 2021: Distribute survey and process results

Q3 2021: Design prototype self-help tool

Q4 2021: Evaluation of the use and usability of the self-help tool

Q1 2022: Implementation and communication

- Launch of the self-help tool among patients, loved ones, and professionals.

- Communication about the research results through various (scientific and non-scientific) media.

References

Burrell, J. R., Hodges, J. R., & Rowe, J. B. (2014). Cognition in corticobasal syndrome and progressive supranuclear palsy: A review. Movement Disorders, 29(5), 684–693. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25872

Brown, R.G., Lacomblez, L., Landwehrmeyer, B.G., Bak, T., Uttner, I., Dubois, B., Agid, Y., Ludolph, A., Bensimon, G., Payan, C., Leigh, N.P.P. (2010). Cognitive impairment in patients with multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy, Brain, Volume 133, Issue 8, August 2010, Pages 2382–2393, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq158

Ceravolo, R., Pagni, C., Tognoni, G., Bonucelli, U. (2012). The epidemiology and clinical manifestations of dysexecutive syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2012.00159

Chapparo, C., Ranka, J., & Nott, M. (2017). Perceive, recall, plan and perform (prpp) system of task analysis and intervention. In M. Curtin, M. Egan, & J. Adams (Eds.), Occupational therapy for people experiencing illness, injury or impairment: promoting occupation and (7th ed., pp. 243-257). United Kingdom: Elsevier.

Foster, E.R., Spence, D., Toglia, J. (2018). Feasibility of a cognitive strategy training intervention for people with Parkinson’s disease. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40:10, 1127-1134. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1288275

Fengler, S., Liepelt-Scarfone, I., Brockmann, K., Schäffer, E., Berg, D., Kalbe E. (2017). Cognitive changes in prodromal Parkinson’s disease: A review. Mov Disord. 2017 Dec;32(12):1655-1666. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.27135

Giguère-Rancourt A, Plourde M, Doiron M, Langlois M, Dupré N, Simard M (2018) Goal management training ® home-based approach for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: a multiple baseline case report, Neurocase, 24:5-6, 276-286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13554794.2019.1583345

Goldman, J. G., Aggarwal, N. T., & Schroeder, C. D. (2015). Mild cognitive impairment: an update in Parkinson’s disease and lessons learned from Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegenerative disease management, 5(5), 425–443. https://doi.org/10.2217/nmt.15.34

Goldman, J.G., Vernaleo, B.A., Camicioli, R. et al. (2018). Cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: a report from a multidisciplinary symposium on unmet needs and future directions to maintain cognitive health. npj Parkinson’s Disease 4, 19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-018-0055-3

Guest, G., Namey, E., & McKenna, K. (2016). How Many Focus Groups Are Enough? Building an Evidence Base for Nonprobability Sample Sizes. Field Methods, 29(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822×16639015

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Kalbe, E., Aarsland, D., & Folkerts, A. K. (2018). Cognitive Interventions in Parkinson’s Disease: Where We Want to Go within 20 Years. Journal of Parkinson’s disease, 8(s1), S107–S113. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-181473

Koerts, J., Tucha, L., Leenders, K. L., van Beilen, M., Brouwer, W. H., & Tucha, O. (2011). Subjective and objective assessment of executive functions in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci, 310(1-2), 172-175. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2011.07.009

Koga, S., Parks, A., Uitti, R. J., van Gerpen, J. A., Cheshire, W. P., Wszolek, Z. K., & Dickson, D. W. (2017). Profile of cognitive impairment and underlying pathology in multiple system atrophy. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 32(3), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26874

Kudlicka, A., Hindle, J. V., Spencer, L. E., & Clare, L. (2018). Everyday functioning of people with Parkinson’s disease and impairments in executive function: A qualitative investigation. Disability and Rehabilitation. Volume 40, issue 20, https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1334240

Kulisevsky, J., Fernández de Bobadilla, R., Pagonabarraga, J., Martínez-Horta, S., Campolongo, A., García-Sánchez, C., illa-Bonomo, C. (2013). Measuring functional impact of cognitive impairment: Validation of the Parkinson’s Disease Cognitive Functional Rating Scale. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 19(9), 812–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.05.007

Ruzafa-Valiente, E., Fernández-Bobadilla, R., García-Sánchez, C., Pagonabarraga, J., Martínez-Horta, S., & Kulisevsky, J. (2016). Parkinson’s Disease—Cognitive Functional Rating Scale across different conditions and degrees of cognitive impairment. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 361, 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2015.12.018

Santangelo, G., Vitale, C., Picillo, M., Moccia, M., Cuoco, S., Longo, K., … Barone, P. (2015). Mild Cognitive Impairment in newly diagnosed Parkinson’s disease: A longitudinal prospective study. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 21(10), 1219-1226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.08.024

Sturkenboom, I. H.W.M., Nott, M.T., Bloem, B.R., Chaparro, C., Steultjens, E.M.J. (2019). Applied cognitive strategy behaviours in people with parkinson’s disease during daily activities: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 52: jrm00010. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2635

Tarolli, C.G., Zimmerman, G.A., Auinger, P., McIntosh, S., Horowitz, R.K., Kluger, B.M., Dorsey, E.R., Holloway, R.G. (2019). Neurol Clin Pract Nov 2019. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000746

Van Keulen-Rouweler, B.J., Sturkenboom, I.H.W.M., Kottorp, A., Graff, M.J.L., Nijhuis-Van der Sanden, M.W.G.M., Steultjens, E.M.J. (2017) The Perceive, Recall, Plan and Perform (PRPP) system for persons with Parkinson’s disease: a psychometric study, Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 24:1, 65-3. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2016.1233291

Van Staa, A., Evers, J. (2010). ‘Thick analysis: Strategie om de kwaliteit van kwalitatieve data-analyse te verhogen. Kwalon, 43, nr. 1, 5-12. https://www.tijdschriftkwalon.nl/scripts/shared/artikel_pdf.php?id=KW-15-1-2

Vlagsma T.T, Koerts, J., Fasotti, L., Tucha, O., van Laar, T., Dijkstra, H., et al. (2016). Parkinson’s patients’ executive profile and goals they set for improvement: Why is cognitive rehabilitation not common practice? Neuropsychol Rehabil 2016; 26: 216–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2015.1013138

Vlagsma, T.T., Duits, A.A., van Laar, T. Annelien A. Duits, Hilde T. Dijkstra, Teus van Laar & Jacoba M. Spikman (2020) Effectiveness of ReSET; a strategic executive treatment for executive dysfunctioning in patients with Parkinson’s disease, Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30:1, 67-84, https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2018.1452761

This research leads to a practical tool for patients and their environment with their own detours to bypass cognitive obstacles as a result of Parkinson’s disease. The self-help tool supports self-management and self-management in a practical way.

The tool is helpful for patients themselves, in conversations between patients and relatives, and also in conversations between patients, partners, and healthcare professionals about (para) medical treatments in the cognitive field. Using the tool, patients can share their preferences and expectations about cognitive strategies with healthcare professionals. Because the detours are linked to the method that occupational therapists use themselves, it becomes easier to clarify the common principles. Healthcare professionals are supported and encouraged through the tool to use methods that reflect the experiences of the patient.

In order to use the tool for these purposes, the implementation not only focuses on the use of the self-help tool by patients themselves but also by care providers, the Parkinson Association and care networks such as ParkinsonNet. Within this project, the relevant partners are represented in the project team and sounding board group. They endorse the potential value of the self-help tool and intend to facilitate its implementation in practice, for example by integrating the tool into the P?HJAE! from the Dutch Parkinson Association and in courses for healthcare professionals.

The self-help tool is made available to Parkinson’s patients, their loved ones, and healthcare professionals as widely as possible, for example by drawing attention to it via ParkinsonNet and popular media such as Parkinson Magazine.

| Matching priorities: | |

|

Cause, disease modification, cure |

No |

|

Parkinsonism |

No, but we have seriously considered including people with parkinsonism. From the scientific literature (e.g. Brown, 2010; Koga, 2017; Burrell, 2014). |

|

(Para-)medical treatment |

Yes |

|

Additional therapies |

No |

|

Diet and exercise |

No |

| Patient skills and personal management |

Yes |

Explanation

Paramedical treatment

This research contributes to a better understanding of personalized intervention options for cognitive problems due to Parkinson’s disease.

Strengthen patient skills and personal direction

This research is carried out among patients and their loved ones themselves, makes an inventory of detours, and then shares these with the patients and their surroundings. This research is therefore pre-eminently aimed at increasing one’s own skills and direction and looks at what one can still do (detour) instead of what one can no longer do (cognitive problems).

|

Necessary: |

Probably the investigation is not WMO mandatory, as it is not invasive in nature. |

|

Applied: |

No |

|

Obtained: |

– |

|

Explanation: |

A qualitative inventory of patient experiences with solutions to problems in daily functioning is not invasive. However, we do have to submit the research protocol to the METC and request an exemption (short procedure). The application must be accompanied by a data management plan in which we indicate, among other things, which data we collect and share why and how we guarantee the safety of the data and privacy of the research participants. |

The research proposed here fits well with:

- The knowledge gained during the training ‘P?HJAE!’ of the Dutch Parkinson’s Association. At the same time, the knowledge gained during this practice-oriented research flows back to the course and the course can be upgraded to ’the next level’.

- The research line ‘Non-pharmacological interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease’ that has taken shape over the past 15 years within the Radboudumc, now with the – still underexposed – dimension of cognitive functioning in daily (work) practice.

- The findings from the COPIED study (detours from a patient perspective) will be valuable in strengthening the patient perspective in the further development of the ergotherapeutic PRPP intervention (personalised cognitive strategy training) for people with Parkinson’s disease and problems in daily practice.

- The improvement of care that is envisaged within ParkinsonNet and the Parkinson Centrum Nijmegen, aimed at strengthening self-direction in care.

- The mission of the HAN research group on neurorehabilitation, which is aimed at setting up and implementing care innovation in practice in order to improve the quality of life of people with neurological disabilities.

Furthermore, the current project fits nicely with:

- Another project submitted by Dr. Annelien Duits and others (subsidy round Parkinson’s Society 2020) in which an online self-management program for PwP – ‘Parkinson’s Patient in Balance’ – is being developed. This program contains various modules with in-depth information and problem-solving skills for themes such as ‘dealing with uncertainties’, ‘balance in activities’, and ‘acceptance’. A (digital) variant of the self-help tool with ‘detours’ we will develop during our research could be a nice addition, possibly in the form of an extra module: ‘dealing with cognitive changes’.

- The research into ‘foutloos leren bij de ziekte van Parkinson by Dr. Dirk Bertens (Klimmendaal)’ to which we can add the patient perspective.

Patient participation takes place at the level of direction and partnership. The question arose from the patients themselves (Marina Noordegraaf and Edwin Barentsen, both patient researchers at the Dutch Parkinson Association). They are the initiators. So, in this case, it is a research project with researcher participation 😉

The initiative arose during a meeting of the patient researchers at the Parkinson’s Society. The reason was the distribution of the poster by Marina and Dr. Jorik Nonnekes – 55 Detours with which Parkinson patients bypass freezing – with 7 compensation categories and 55 detours to bypass physical freezing. Marina and Edwin imagined the importance of such a poster for ‘cognitive freezing’. Both experience the cognitive problems in their Parkinson’s as a greater handicap than the physical symptoms.

Based on the need to tackle this methodically and scientifically, they contacted Dr. Ingrid Sturkenboom, an expert in occupational therapy for Parkinson’s disease, and Dr. Esther Steultjens, an expert in daily actions, cognition and cognitive strategy training.

Part of this project is that Marina will follow a basic course in ‘qualitative research’ and thus invest in her value as a patient researcher for the Parkinson’s Society.

| Total | € 40.000 |

|

Of which staff support |

€ 32.500 |

|

Of which material support |

€ 7.500 |

| Short explanation staff |

€ 7.200 | Project supervision € 23.800 | Research, research assistance, design € 1.500 | Travel and expense reimbursement for research participants (focus group and interviews), HAN students and members of advisory board |

|

Short explanation material |

€ 3.000 for sharing the research process and research results (open science, e.g. pre-registration, sharing of research process via blog, sharing of data, publication of an open access article). € 3.000 for the (prototype) self-help tool and its distribution to patients. € 500 for a course on methods and data analysis in qualitative scientific research. € 1.000 for ParkinsonNext (for advertising the survey). |

This research will be carried out in the Netherlands and will lead to ‘Dutch data’. Still, I thought it would be useful to share what we are doing in at least the English language too. You never know how projects in all the other nice places in this world could cross-fertilize with ours.

Do you already have input, ideas, wishes? Let me know!

Furthermore, the addition of ‘Part I’ in the title of this blog post speaks for itself: You can count on me to keep you informed!

Sparks

Sources

Mietchen, D. (2014). The Transformative Nature of Transparency in Research Funding. PLoS Biol 12(12): e1002027. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002027 (Open Access)

Vaesen, K., & Katzav, J. (2017). How much would each researcher receive if competitive government research funding were distributed equally among researchers?. PloS one, 12(9), e0183967. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183967 (Open Access)

Hi Marina

this project sounds very exciting and very much needed research! I agree their is often too much focus upon movement and freezing.

I eagerly await the outcomes of this project as an Occupational therapist working in a Parkinson’s Team in the UK.

I would like to use two of your photo images for a Parkinson’s online education group that we are creating for newly diagnosed people with Parkinson’s which would usually be done face to face but we now need to deliver this online due to current pandemic.

Your pictures demonstrating what you need to j’uggle in life with Parkinson’s’ and also the one where you demonstrate ‘cognitive detours for freezing of thought’ would suit my presentation well.

I will reference your source as requested but I wondered if there was a download version of the cognitive detours?

Regards

Debra

Hi Debra,

I will gladly let you know the outcome of this research project. Currently, I am only doing updates in Dutch (https://copiedstudie.nl).

Just uploaded the cognitive detours for freezing of thought image on my Downloads page.

I hope it will suit your needs. I am very curious about your educational material for the newly diagnosed. I would love to see it sometime. Maybe we could benefit from your work in the Netherlands too.

Best wishes,

Marina